The European Commission has decided to pursue an investigation to assess whether BMW, Daimler and the VW Group (comprising Volkswagen, Audi, and Porsche) colluded to avoid competition on the development of cleaner emissions technology.

The foundation stone of the EU antitrust rules is Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union – the article plainly prohibits “all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market”.

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

20px

center

Andrew Kyprianides themobility.club

writer-image

20

default

Heading

WHAT HAPPENED?

center

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

0px

Text

The first inspections were carried out almost a year ago, on October 23, 2017 – the Commission has confirmed that those raids on the premises of German manufacturers were in relation to the cleaner emissions collusion scandal that has just surfaced.

According to the press statement from the European Commission, there are suspicions that the five automakers agreed to avoid competition on the development and roll-out of technology to clean the emissions of petrol and diesel passenger cars. The technology examined includes selective catalytic reduction (“SCR”) systems to reduce harmful nitrogen oxides emissions from passenger cars with diesel engines; and “Otto” particulate filters (“OPF”) to reduce harmful particulate matter emissions from passenger cars with petrol engines.

As the manufacturers’ respective websites and other sources reveal, these technologies have only recently been introduced, and their introduction is normally limited to the high-end of the carmakers’ fleet. BMW, for example, made the SCR catalytic converter (part of its BluePerformance Technology package) a standard feature of all BMW diesel models in March 2018 – it was reportedly a £995 option on some diesel passenger cars before then. Mercedes-Benz used the Otto Particulate Filters in its S500 (a premium vehicle costing nearly £100,000) and has promised to introduce the technology to other models from 2018. Although unsurprising in hindsight, Volkswagen also introduced the same technology to its petrol vehicles last May, 2018.

Although the details of the potential collusion have not been disclosed by the Commission, the press statement mentions that the five automakers “may have violated EU antitrust rules that prohibit cartels and restrictive business practices, including agreements to limit or control technical development”. The almost concurrent rolling out of the cleaner emissions technology by the manufacturers in question could, for example, have been a product of collusion aimed at delaying the development and/or introduction of the cleaner emissions technologies, although this is merely a guess, amid the lack of further information.

Although this -potential- wrongdoing comes in the wake of the Dieselgate scandal, the Commission took extra care to clarify that “at this stage, there is no indication that the parties coordinated with each other in relation to the use of illegal defeat devices to cheat regulatory testing”.

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

10px

Heading

WAS IT ALL ILLEGAL?

center

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

0px

Text

No. As the Commission clarifies, there were other topics discussed during these “Circle of Five” meetings. Among other issues, the automakers discussed things like the speed at which their respective cruise control systems should operate, the speed at which convertible cars’ roofs open and close, and potential cooperation in improving testing procedures for car safety (the European Crash test, known as the EURO NCAP.

These discussions could have also constituted anti-competitive behaviour, although the Commission is not investigating that behaviour at the moment. Anti-competitive behaviour could be found if, for example, the automakers agreed to improve their cruise control systems and pass the costs for this improvement to the buyers, by agreeing on the pricing of their advanced cruise control systems (thus depriving the consumer of their right to a competitive market).

It should be noted that according to the European anti-trust rules, competing parties are allowed to discuss and/or cooperate to improve the quality of their products. What is not acceptable, though, is the collusion to stifle technical development and/or rolling out of improved technology.

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

10px

Heading

WHAT COULD HAPPEN?

center

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

0px

center

Text

Since taking over in 2014, Margrethe Vestager, the European Commissioner for Competition, has not held back when it comes to investigating possible collusion between competitors. Most notably, she has spearheaded the investigation efforts that led to nearly $4 billion of fines imposed on truck makers (Volvo/Renault, MAN, Daimler, Iveco, DAF, and Scania) after the notorious, 14-year long cartel they participated in was uncovered.

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

0px

Text

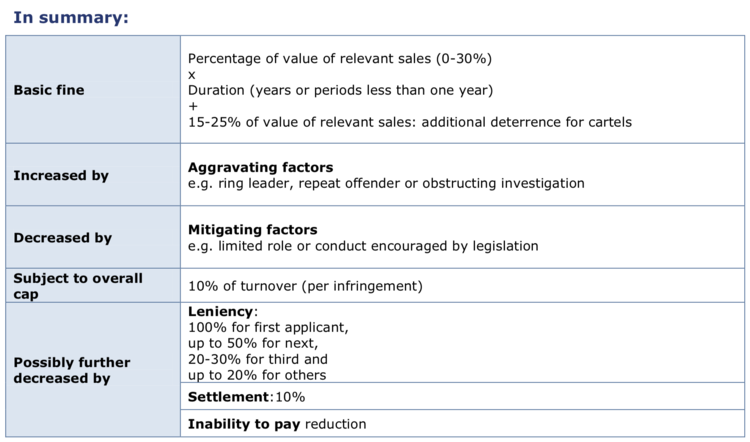

The Commission is armed with a powerful weapon: the fine imposed for each infringement, if collusion is proven, could amount to up to 10 percent of each company’s annual turnover. Mercedes Benz, for example, could be fined up to €16.43 billion, representing a 10 percent cut of their 2017 turnover of €164.3 billion. Just for perspective, the net profit of the Daimler group for 2017 was €10.9 billion – which means the Commission could impose a fine that is higher than the group’s annual profit. Although this may sound like a “ceiling” fine, which is rarely imposed, the European Commission has taken a hard stance against wrongdoers: SCANIA, the Swedish truck maker that was found guilty of participating in the truck cartel, refused to settle, thus losing any access to the leniency programme and/or the “settlement” discount of 10 percent. In 2017, it was fined €880 million, representing approximately 8% of global turnover for the year – indicatively, the net profit of SCANIA for 2017 was approximately €850 million.

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

0px

Heading

WHAT SHOULD HAPPEN?

center

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

0px

Text

Last May, 2018, the Commission referred France, Germany, and the United Kingdom to the Court of Justice of the EU for failure to respect limit values for nitrogen dioxide (NO2). If the collusion is proven, it will become clear that a large percentage of European buyers of passenger cars were, in one way or another, deprived of their right to cleaner emissions technology – one of the devices included in the purported cartel is SCR, a system that can massively reduce emissions of nitrogen dioxide.

The five investigated automakers command approximately 40% of the European car market – it is evident that their contribution to the passenger car-related pollution is similarly high. If the investigation leads to the imposition of fines, it will be reassuring to see the proceeds used to further encourage the uptake of zero emissions cars. Admittedly, the European Union does not earmark the proceeds from fines for particular purposes: as carmakers selling cars in Europe will have to conform to much stricter CO2 emissions standards from 2020 though, the creation of an additional pool of money to fund new EV infrastructure and zero-emission vehicle purchase incentives could be facilitated through the collection of large amounts of money as fines.

It remains to be seen whether collusion will be proved and to what extent the manufacturers will fall victims to the wrath of the antitrust authorities of the European Union.

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

0px

Text

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Andrew Kyprianides is a Cyprus-born individual who completed his Law degree at King’s College London in 2015. After graduating from a Master’s in Public Policy at Harvard University in 2018, he decided to focus on a rapidly changing part of the commercial world: mobility. Through his website, themobility.club, Andrew explores the developments in all things directly or indirectly related to mobility – autonomous vehicles, first/last-mile transportation solutions, AI, Waymo, Cruise, Tesla, curb space data, patents, regulation, and city planning, among other things.

themobility.club

themobility.club is a platform which allows readers to stay in touch with the latest mobility-related developments in various ways: the integrated Twitter feed provides instant updates on what is happening at the moment, the Daily articles provide an overview of what happened throughout the day, and the in-depth Spotlight articles allow a deeper understanding of the latest headlines. The weekly newsletter of themobility.club offers a quick way to stay in touch with the most important news of the week.

no-repeat;center top;;

auto