With tech companies preaching the advantages of artificial intelligence, cloud technology and machine learning, the term ‘blockchain’ has also been bandied around in a bid to enhance productivity.

Blockchain has been considered “one of the most disruptive innovations since the advent of the Internet” with global business benefits estimated at US$21 billion by 2021.

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

center

Kaveesha

Kaveesha ThayalanTCLA Writer

writer-image

Title Author

Yet – what exactly is it?

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

0px

large

https://www.thecorporatelawacademy.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/shutterstock_772185664.jpg

Title Author

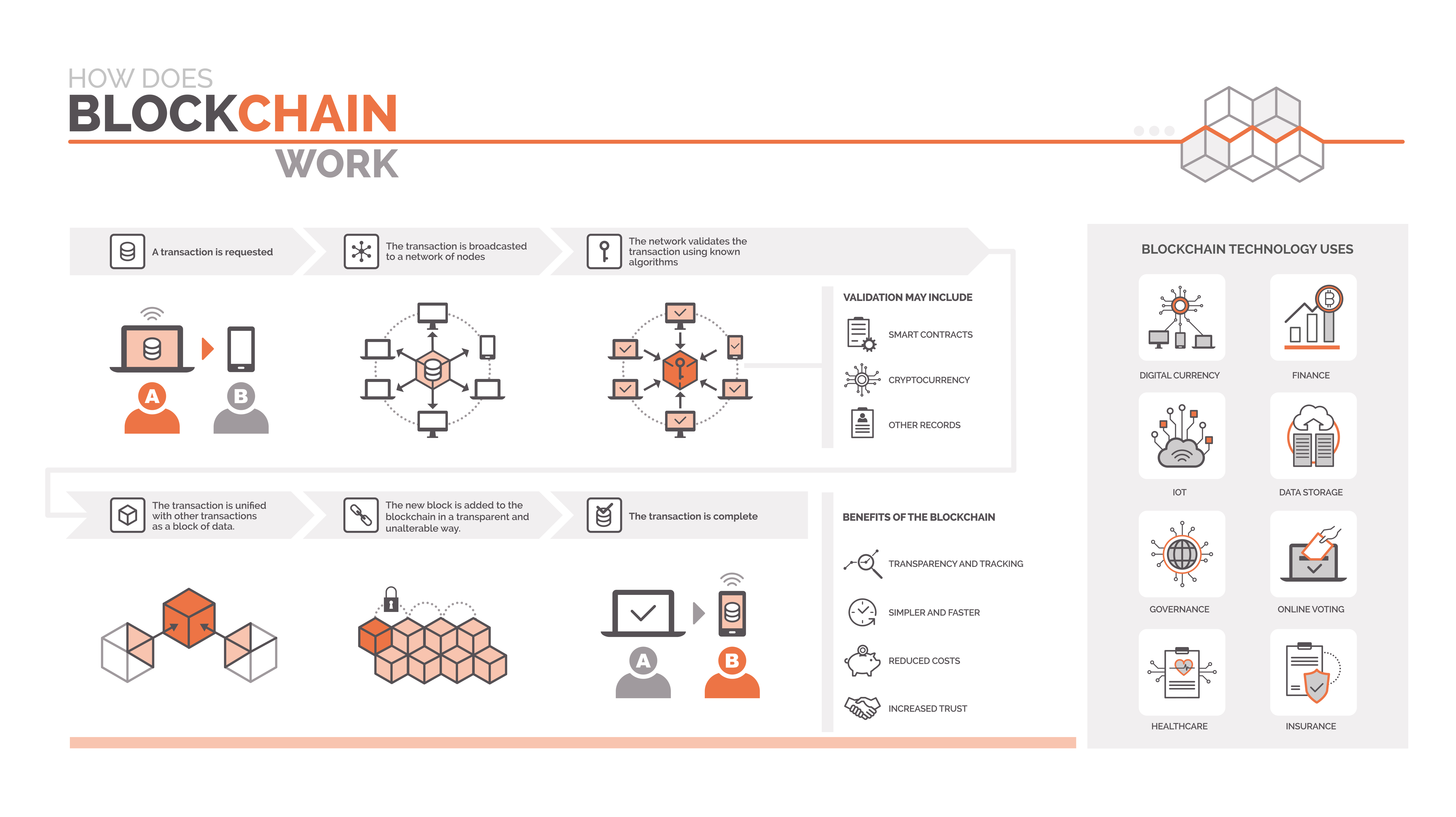

To put it simply, blockchain is a chain of digital blocks which contain data. When data is recorded, a ‘hash’ is created; this identifies the unique contents of the block akin to a fingerprint. When a new block is added to the chain, it contains its own hash and the hash of the previous block to ensure a connected chain. The record of data is shared across all nodes (participants) and is not centrally stored in any single location. Across various industries, the use of blockchain technology to record data is gaining prominence primarily due to its security, efficiency, and potential cost savings.

Trust and security

Information on a blockchain is immutable and secure due to its hash function. A change of one block’s contents would change its hash and disrupt the subsequent blocks which still contain the previous hash. For the change to be accepted, the hash of all subsequent blocks would need to be recalculated.

The distribution of the record of information amongst all its nodes (participants) furthers immutability. Compared to a traditional ledger system, no node enjoys special rights to make a unilateral change to the record. Any changes to the chain will require a consensus from other participants that the change is valid so that that it is recognised in the ledger. This characteristic hinders a centralised hacking attack as corruption of data requires a simultaneous change to all the blocks in the chain.

This self-auditing process increases trust in the system due to the transparency, verifiability, and immutability of data which overcomes issues of hackability and manipulation that persist in traditional digital systems.

Efficiency

The use of blockchain is also considered more efficient due to the accuracy and speed at which information can be input and transmitted which arises from a decentralised authority. A decentralised authority results from the consensus-based system of storing information. Without a central authority to verify information or complete transactions, risks and error-rates can be minimised. This increases the speed which decisions can be made, and information authenticated. By eliminating third-party intermediaries, verification and transfer of data can be completed more efficiently. To capitalise on this, Maersk and IBM created TradeLens Blockchain Shipping solution which moved its global supply chain on to a blockchain network and increased the efficiency of moving goods across the 234 participating marine gateways.

Cost savings

The increase in efficiency creates cost-savings for implementers as it reduces the cost of connections and transactions. Compared to a traditional recording system, it requires minimal overhead costs with fewer intermediaries to manage as the transfer and verification of data is completely automated. As a result, companies can avoid paying staff to input and verify data. In the investment market, it is estimated that the switch to using blockchain from a laborious paper system could save asset managers US$2.7bn.

Application

The use of blockchain is currently trialled across various sectors, from energy to agricultural industries. Looking to the legal market, firms are experimenting with blockchain to maximise its benefits. In an industry which is centred around identifying and mitigating significant risks, trust is paramount between firm and client. Blockchain has the power to strengthen firms’ relationships with clients due to the transparency and accuracy of data collection and use. The application of blockchain could also minimise the need for simple administrative tasks such as data gathering and verification, thereby reducing overhead costs and financial outgoings while improving cash conversion.

Firms are independently implementing blockchain technology within their operations. For instance, K&L Gates has invested in Chainvine to decentralise the company’s data system in order to create a secure and permanent blockchain ledger system. Chainvine also aims to create ‘intelligent commodities’ to enable more efficient recording of asset data. Several other firms including Herbert Smith Freehills, Freshfields, Kennedys, Fieldfisher and Hogan Lovells are also dedicating resources to exploring the potential applications of blockchain within their firms.

Firms are also working together to establish a common blockchain system within the legal services market. In February, ten law firms joined R3’s legal blockchain research community, ‘Legal Centre of Excellence’ (LCoE); Ashurst, Baker McKenzie, Clifford Chance, Crowell & Moring, Fasken, Holland & Knight, Perkins Coie, Shearman & Sterling, Stroock, and White & Case. The collective participation of law firms is paramount to ensuring the widespread adoption of the technology.

Smart contracts

A key application of blockchain in this market is through smart contracts. Smart contracts are essentially contracts that are drafted through code. These automatically trigger an action once an event has been marked as completed. This can be illustrated simply with a property sale agreement; once conditional events are fulfilled (e.g. the payment is made), the smart contract will automatically trigger the transfer of property to the buyer on the property register. In this ‘living contract’, once a conditional event is identified, trusted data sources called Oracles track the progress of the real-life event and enable the performance of the contract. Oracles are supplied by third parties and can constitute a multitude of official and trusted sources.

Smart contracts benefit from certainty that is entirely self-contained in the code. Contracts are made more efficient with the speed at which an exchange of value is enabled due to trustless execution. There is no need for an external authority to authorise a subsequent action after the fulfilment of the event as it is completed automatically. The security embedded in a blockchain transactions also reduces fraud and improves data accuracy.

One of the most prominent developers of smart contracts is Ethereum. Assets can be traded on the Ethereum platform with the use of Ether or other cryptocurrencies built on Ethereum. Using the Solidity code, individuals can self-serve by coding their own contracts on the platform. Specifically, in the legal market, R3’s Corda is another platform on which smart contracts could be built. Chainvine’s development of ‘intelligent commodities’ would also advance the development of a smart contract platform to enable efficient transactions of assets.

Considerations

However, amongst all the praise, it is important to consider potential risks of present smart contract applications.

First, smart contracts are difficult to code correctly. Due to its immutable nature; once written, the contract is irreversible. If the data input is inaccurate, this would create a cascading effect across the performance of the contract. Smart contracts might not be suitable for complex transactions due to the various uncertainties of contractual terms in a complex agreement which make coding difficult. Contracts would need to be drafted unambiguously and without any room for interpretation to ensure the parties’ intentions are accurately fulfilled. Traditional ambiguous terms such as “reasonable efforts” would need to be expressly defined as codes cannot interpret language. The LCoE recognises this problem and is currently working towards linking data to associated legal prose to ensure code is rooted in law. However, until this is established, smart contracts are limited to simple transactions.

Second, the legal nature of smart contracts is disputable. In common law systems, establishing a contract requires offer and acceptance, intention to create legal relations, considerations, and certainty. Without human intervention in smart contracts, parties’ intentions to create legal relations are uncertain as coded performance is automatic. This would be a significant issue with “follow on” contracts if performance of a previous contract automatically creates a subsequent contract without the awareness of parties. Ideas of consent and agreement through signing would need to be redefined to give legal status to smart contracts. Additionally, special attention needs to be given to contracts established in markets with strict regulations. For instance, financial regulations would need to be coded into the required contracts in order to achieve legal compliance and operational continuity. Presently, the legal nature of smart contracts is uncertain and greater legislative guidance is required to ensure blockchain commands translate into legal obligations.

Third, smart contracts might create data privacy issues. A strong selling point of smart contracts is its immutable security. However, this is at odds with current General Data Protection Regulations which implemented a right to be forgotten and data migration. The permanent record of sensitive personal data would be problematic, especially since transactions are largely transparent. To minimise privacy disruptions, the blockchain would need to be altered to limit visibility of transactions only to “trusted” nodes. Total removal of data would be difficult on a blockchain and technology-based solutions need to be developed to bring smart contracts in line with data regulations.

Fourth, a smart contract’s inherent security is undermined if there is a bug in the code. In 2016, the Decentralised Autonomous Organisation (DAO) hacking attack resulted in the loss of 15% of all Ether in circulation at that time (3.6 million Ether). To prevent more funds from being lost, a “soft-fork” proposal was put forward which essentially froze assets and prevented Ether from moving out of the DAO. In this case, the fork approach was a one-time fix to this particular vulnerability. To improve security in smart contracts, several tech companies are developing security infrastructure to prevent similar DAO incidences. For instance, Quantstamp is developing a security-auditing protocol which enables peer-submitted verification software and “Bug Finders”. However, this labour intensive idea undermines the speed and efficiencies of blockchain. With any code, it can be argued that bugs are inevitable due to human error. Until scalable security can be guaranteed, smart contracts could create unnecessary risk and liability issues for firms.

Future

Regardless of the aforementioned considerations, the blockchain craze within the legal industry does not seem to be slowing down. In fact, firms are increasingly exploring the application of blockchain so as not to lose innovation points in a highly competitive environment. While smart contracts have the power to cut lawyers out of the picture, firms could remain relevant by evolving their services.

Smart contracts cannot be drafted without the legal knowledge which underpin legal compliance. Regulations would need to be considered to ensure coded contracts can be performed. Legal drafting would still be required before contracts can be made into code. Lawyers would also need to identify and carve out clauses of a contract which require greater flexibility and human interpretation, such as force majeure events. As a result, the legal profession might move towards a more advisory role, focussing on value-added services which require creativity and innovative thinking. Moreover, establishing strong client relationships cannot be automated and lawyers will remain paramount in managing clients and their individual requests.

Conclusion

Blockchain could very well be the long-awaited disruption to the largely stagnant legal industry. It is argued that the use of blockchain could consolidate legal services and erode firms’ margins as services could be delivered at a fifth of current costs. In line with Richard Susskind’s predictions, the commodification of legal services could be executed through disruptive blockchain applications such as Dapps which facilitate commercial smart contracts without the need for law firms. In a “more-for-less” future, ignoring blockchain is likely to be corporate suicide and law firms should innovate or risk irrelevance.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

no-repeat;center top;;

auto

0px

Introduction

Kaveesha is a member of TCLA’s writing team. She recently completed her LLM in Intellectual Property Law at Queen Mary, University of London.

You can reach out to Kaveesha in our forums by clicking here.

no-repeat;center top;;

auto