Private Equity, Private Equity, Private Equity; how often do we hear this “buzzword” thrown around? How often do these two, apparently simple words, cast an aura of doubt (amongst the less financial-savvy of us of course), whenever they are spoken? How often have you seen them in big bold letters starting back at you in the front pages of the FT, almost challenging you to keep on reading? And how often, having read the article, do you still feel like you’re back to square one?

Well, for me personally this process used to be pretty cyclical. After listening to a private equity-focused conversation, or after unsuccessfully skim reading a PE news story, occasionally looking up some of the harder terms (high-yield bonds, mezzanine debt, leveraged acquisition) on Investopedia, I became so frustrated with my lack of understanding that I gave up and decided to keep opting for the “nod and agree” strategy.

Then I decided that, like many things in life, if I really wanted to have a grasp of how this asset class worked, I had to dedicate some real time and focus to the matter; some half-hearted, occasional attempt would definitely not suffice. So, after an intensive self-taught few sessions, here I am. What I am hoping to do in this article is to outline how this industry developed and came to be, who the players in it are, how it fits in into the greater economy and ultimately how it works.

Introduction to Private Equity

A textbook definition of private equity would define it as an asset class where private equity firms (also called “sponsors” or private equity houses) invest in securities of private or public firms (meaning shares of companies) with the aim of acquiring a minority or a majority share. Once the company is acquired, private equity houses use their operational and managerial expertise to increase the company’s profitability in the medium to long term and eventually exit their investment, cashing in the money.

Having given you this definition, does it all make sense to you now? No, probably not. A lot of question marks still inevitably linger between those lines: What is a PE house? How is it structured? What kind of companies do they invest in or acquire? Where do they get all the money to do this from? Why would a company’s board be willing to let an outsider in and give away its autonomy? How do these people even make the money?

What is a PE fund? How is it structured? Who invests in it?

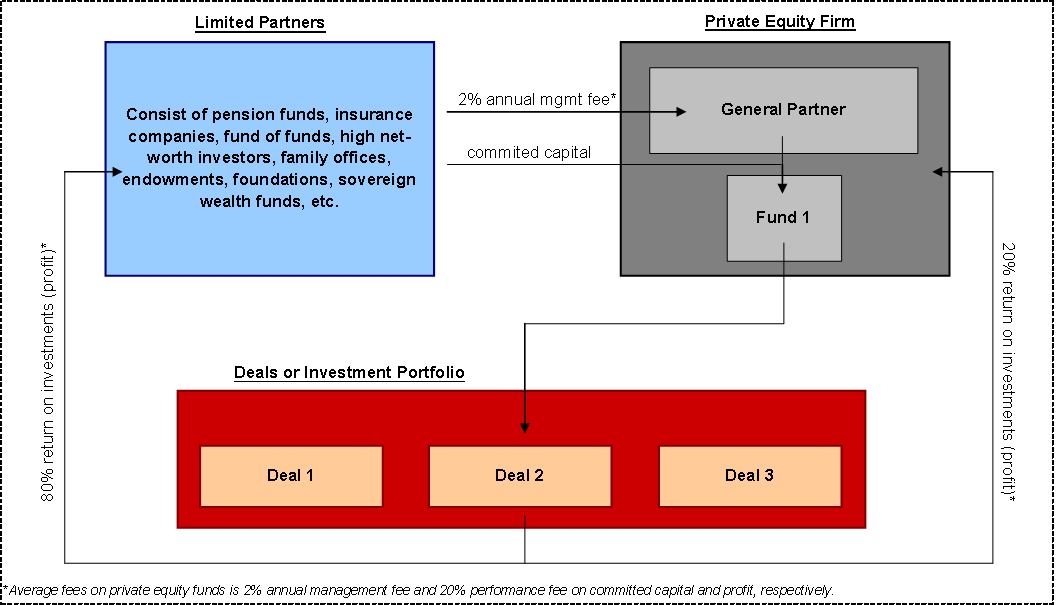

In order to be able to acquire stakes in company, private equity houses will need money to buy the control they want, and this money is taken from their “fund”. Fund money is given by investors who decide to invest in it, thus becoming “limited partners” of the private equity house, which is ran by a number of professional asset managers. The private equity house, essentially represented by the managers, is known as the “general partner” or GPs of the fund, whereas the other investors are the limited partners (LPs). This partnership is known as a “private equity fund”.

LPs can be pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds and high net-worth individuals, which entrust their money to the fund hoping to share in the eventual higher returns that riskier investments could yield.

The essential difference between a GP and an LP is that the former owns the fund and the latter is more of a “silent partner” in the business. A GP is someone who actively runs and manages the day-to-day operations of the company and who can act on its behalf. On the other hand, the LPs are not involved in the daily management of operations and don’t participate in management meetings. However, whereas the GPs are burdened with unlimited financial liability, meaning there is no limit to the amount they will have to pay out if, for example, the fund goes under or an investment doesn’t work out, an LP\’s liability is limited to the amount of capital they contributed to the fund in the first place.

However, for every risk, there is often the potential for a reward, and if huge losses are on one side of the equation, potential mammoth profits are on the other side, especially if the transaction is financed with debt (we’ll get back to that later). So, if the private equity house lives up to expectations, everyone gets a piece of the profit when the investment is “exited”. GPs usually make money from the famous “2 and 20” combination; they take 2% in management fees and 20% of performance fees, also known as a “carry fee” (taken from the exited investment). But, before GPs are entitled to their fees, LP’s must receive a specified % rate of return, which is typically between 8-10% , 8% of which goes to the LPs and the remaining 2% goes to the GP’s . This structure exists so that private equity firms are actually motivated to make these returns and their interests ultimately align with the LPs. No returns, no fee. Clever incentive scheme right there.

The lifecycle of a fund is usually at least 10 years, during which time around 10-12 investments are made. When the fund is eventually closed up, GPs have to buckle up and start looking for more cash from investors in order to raise fund money and start the process all over again (if their success rate is good, this part shouldn’t be a problem).

Ok, so now that we’ve established what a private equity house actually is and how it operates, it makes sense to start thinking about what kinds of companies these companies buy stakes in. And here is where it gets a tiny bit more complicated, because companies targeted by a private equity house can range from startups, to mature companies and distressed companies.. Depending on what type of target companies the fund decides to “specialise” in, they will end up walking down a specific private equity avenue with different aims and objectives in mind. In fact, private equity can essentially be divided up into three different “branches”.

Types of private equity investment

1) Venture Capital (VC)

VC is a kind of private equity investment strategy where a private equity firm chooses to funnel its capital into young and promising startups which they believe have a future. They provide the startup with the “seed fundraising” capital they need to get started, take a minority stake in the company and hope to cash out their investment if and when the latter becomes successful.

2) Growth Capital (GC)

Although we don’t’ often read about this private equity branch in the press, probably because it lacks the thrill of uncertainty and risk that are associated with VC investments and LBO operations (see below), GC operations still deserve their fair share of attention. GC can be envisioned as a midpoint between VC, where money is channeled into young companies, and LBO’s, where money is used to invest in mature companies and turn them around. However, unlike VC investments where private equity firms take a minority stake, in growth capital they can opt for either a majority or minority stake. Growth equity will be preferred when owners and directors of a target company don’t yet believe that the company has hit a point of no return and has to be sold. Rather, they think it would be more prudent to inject it with some more liquidity (essentially give it more cash to spend) and expertise, both elements provided by the private equity house. Growth-focused private equity firms usually go for transactions which are valued between $10-100 million and by working with the management team they help create value through accelerated operational improvements and revenue growth.

3) Leveraged Buyouts (LBOs)

Last, but definitely not least (in fact this is the most common type of private equity investment!), is the famous leveraged buyouts. This is the branch of private equity which I will devote the most attention to. Why? Because it is the only one which flaunts the “go big or go home” kind of deals, and as a result, it lures along all the biggest players in the financial industry (biggest investment banks, biggest law firms, biggest PR firms), AND the biggest fees.

Burrough and Helyar, authors of what is probably the most read business thriller of all time, “Barbarians at the Gate”, would tell you that “the basics of an LBO are relatively simple”: a PE house, specializing in LBOs, works with the management of an underperforming target company in order to buy it using money which has been borrowed from banks, institutional investors and other subordinated lenders*. Essentially a leveraged buyout is an acquisition which is financed using a large amount of debt and little equity. Post-acquisition, the PE house is supposed to do its job, in other words, it uses its expertise to turn the company around. As this new company starts doing better the debt is eventually paid down with the cash flow produced from the new company’s operations.

To be fair, that does seem easy. However this definition was originally given back when takeovers were rarely hostile and when acquisitions weren’t heavily financed with piles of “junk bonds” (popularised by the US financier Michal Milken), today often cited as the biggest culprits for corporate America’s debt. However, before we even start talking about how LBO’s have gotten more complicated with the years, it might be useful to take a step back and understand how leveraged buy-outs actually developed (I told you this article would go all out, so if you’re still keen on getting the big picture, keep reading!).

Life pre-LBOs

Before this Wall Street wizardry was invented, when deciding what to do about an underperforming company, owners and managers had three options:

Remain privately held. Although, if the company had been stagnating for a while, this seemed like a pretty lousy option. Who wants to keep topping up losses year by year? No one.

Sell shares to the public. This means you are at the mercy of an ever-changing stock market. And supposedly if the company wasn’t doing well in the first place, no good analyst would give your stock a positive rating, meaning no clever investor would actually buy it. So you’re back to square one.

Sell out to a larger company. Again, this would produce short term gains but could prove disadvantageous in the long-term. You lose operating control of the company which might have still had some potential in it.

Therefore when KKR pioneered LBO’s, everyone was happy. Henry Kravis, founder of KKR and back in the day also known as the “buyout King of Wall Street”, once described LBOs as the only way that company executives “could have their cake and eat it too”. No matter what form the LBO took, this operation looked to be a win-win for everyone. The PE house would receive the management and performance fees, shareholders would (hopefully) see the value of the company shares go up, and the board would either acquire a stake in the company or would profit from its improvement in the long term.

If you were paying attention, you will have spotted that I said “no matter what form the LBO took\”. An LBO can, in fact, take many different forms, depending on what method of investment is chosen.

Forms of a Leveraged Buyout

1) Management Buy-Out (MBO)

A management buyout can take the form of an LBO. This is a method of investment where the existing managers of the target company want to buy out the company and exert control by taking a majority stake in it. In this kind of scenario, the management team does not have enough cash to do so alone, thus they usually get a PE fund to partner up with them and co-invest by taking a minority stake, and promising the latter a profit share in the fund. On the other hand, the management team hopes to reap financial rewards offered by ownership by using their knowledge of the company to promote its future growth. MBO’s differ from IBO’s (see below) because in the former less debt is used when acquiring the company, thus giving the new company more financial flexibility.

2) Management Buy-In (MBI)

In this case an external management team is assembled with the aim of ousting the old managerial team, purchase a majority stake in the target company and run the target company post-acquisition. Although PE funds are also involved in MBOs, their preference may sway towards MBI’s where the managers who are brought in to acquire the company is personally known to them.

3) A Buy-In/Management Buy-Out (BIMBO)

This has nothing to do with the pejorative term ‘bimbo’, rather it represents a method of investment where a combination of existing managers and external managers take a controlling stake in the target company.

4) Institutional Buy-Out

By now you should know that the best, or to be more specific, “most common”, is saved for last. It is so common that people have come to equate institutional buyouts with LBOs. However, typically, all of the above are subsets of LBOs (ie they all represent different ways of acquiring stake in companies with external investment, potentially with less debt). In this investment method, it is the private equity fund who purchases either the whole, or a controlling stake in the target, thus calling the shots. The company will still require some sort of management team to run after the transaction has been completed, at least until they exit the investment. The management team can either be formed by the existing one, a new one or a combination of the two. In order to incentivize the management team to do their job, the PE fund will give them minority stakes in the business. These stakes are also known as “management stock incentives” and, as Henry Kravis pointed out, they seem to “do wonders for management’s ability to run the business more efficiently”.

What makes a company vulnerable to an LBO/IBO?

Earlier I mentioned that to be “eligible” for an LBO, so to speak, a company must be underperforming. Interestingly, this does not mean that LBOs will be operated only on companies which are almost on the brink of failure. I mean, sometimes that IS the case, but more often than not, LBO’s target public companies which have a low stock value yet show great profits, pristine balance sheets and good returns. At this point, the inevitable question arises: how do you reconcile a company that makes a profit but has a low stock value on the public markets?

This could be because:

Analysts see no future in the company

Competitors are developing better products in a more efficient manner

Debt is outside normal parameters (ie the company has more debt than profit).

Any of these factors, or even worse, a combination of them, could cause the stock of even the most profitable company to plummet. If this is the case and if it seems the company won’t pick up again, then going private is a good idea as de-listing means you don’t need to account to the public, and as a result you don’t have to comply with onerous rules and regulations. You can streamline operations, improve profitability and ultimately make the company healthy again.

Whether the company is on the brink of failure or just wishes to prop up its share value for the sake of its shareholders, ALL businesses targeted and taken private by private equity funds must show some level of potential. Usually, good candidates have a strong market position and sustainable business models and have businesses which flaunt stable and recurring cash flows. A strong management team would also be ideal, as when the PE fund acquires the company it would prefer someone competent to be on its board. However this is not a must as the fund has the ability of bringing in its own managerial team if it so wishes.

Once a suitable company has been identified, whoever wants to acquire it or is bidding for a majority stake must decide on an amount for the share purchase price. Essentially, how much do they think each share is worth? When estimating this number, bidders must be ultra-careful, as even an extra dollar on the share price could make a massive difference on the overall offer and would further drive up the levels of debt finance needed, meaning more repayments have to be made to get equal. For instance, KKR’s last offer for RJR Nabisco went from $108 a share to $109; this one dollar increase on share price cost the PE house an extra $250 million on the overall price. That’s a pretty big increase, and that is why it is crucial to get the offer price exactly right. The bidder must acquire all the financial data necessary to analyse future cash flow projections of the target company. How do they do this? Well their best shot is asking the company’s current management team who have access to every nook and cranny of the business. When the company is being acquired with the consent of management this process is easy breezy, but when the takeover is hostile this can be very very tricky as management may be reluctant to give the PE house any useful information as this could ultimately work in their disfavor.

Debt

Now, considering the word has been mentioned a considerable amount of times, is the part where I discuss “debt” and the central role it plays in LBOs. Up until now, the main focus has been on the buyout part of an “LBO”, which, to be fair, is the part which best describes the fate of a company subject to such a transaction. However, the “L” in LBO is equally, if not more important. Indeed, without leverage, this whole concept would not work.

As you have probably gathered by now, leverage is DEBT. To be precise, in an LBO, leverage means an above normal amount of debt, and that is why it is worthy of our attention. A transaction is said to be highly leveraged when at least 50% of resources used to finance the acquisition are liabilities, as opposed to being “equity” (aka REAL cash). Why, you might ask, would someone choose to buy a company with debt and in a way, have their hands tied before they even become owners? Well, for starters no one individual is likely to have enough cash to acquire one whole company. For example, the most famous takeover deal in private equity, saw RJR Nabisco go to KKR for the eye-boggling price of $25 billion. Post his divorce, not even Jeff Bezos, might have that sort of money. Further, although financial players such as investment banks or private equity houses have that kind of capital, they certainly wouldn’t be reckless enough to spend it all on one acquisition. This is why risk management and diversification exist.

Secondly, and most importantly, leverage has the capacity to increase the rate of return for equity investors (ie those who have put in real cash). Also, the success of PE houses is measured against their IRR’s, ie their “internal rate of return”. The higher the returns they can make on an investment, the better, and because the potential profit margin to equity investors increase the more leverage is used, it is safe to say that parties to an LBO are not scared of using debt.

To put the effect of leverage on profits into practice, let’s use an example. Say a company is valued at $100,000 and you pay for it all in cash (ie equity). Somewhere down the line you manage to increase the company value and re-sell it for $200,000. This means you have made a 100% return, which is not so bad. However, say you buy the company using a different capital structure. You pay $25,000 in equity and you borrow $75,000. When you sell the company, because you only put in $25,000 of your own money, you will have made a 400% return on your original investment, which is even better.

Obviously keep in mind that the above example has ignored the hurdles posed by the risk that the transaction does not work out, as well as the burden of interest payments when relying on debt. Indeed, debt always comes with interest payments which have to be met regularly. Defaulting on even one payment could cause the whole operation to blow up, leaving equity investors with nothing.

To be fair, it makes sense that there are some downsides; if using leverage always guaranteed those sort of profits, literally everybody would be knocking on the doors of the private equity industry. PE is for the thick skinned, risk-takers of this world.

Where does the debt come from?

When LBO’s first started, this was the usual capital structure used in an LBO transaction:

60% of the capital was loaned by banks (debt)

10% was put in by the PE house (equity)

30% was put in by institutional investors such as pension funds (debt)

When lending such large sums of money, banks will ask for “security” or “collateral”, in order to ensure they will be repaid if the borrower defaults on the repayment. Because they are secured lenders, they also rank first in the priority order of repayment in case of financial difficulties. This is why they are called “senior debt holders”.

If you’re thinking this sort of operation is risky and the amount of debt exceeds the boundaries of your comfort zone, let me tell you that the structure I outlined above is as safe as it gets when it comes to LBOs. In fact, such structure was common back in the 80s when LBO’s had just started and before Milken’s “junk bonds”, using love island lingo, “turned everyone’s head”.

What are junk bonds?

Quoting Investopedia, a bond is a “debt or a promise to pay investors interest payments and the return of the original investment in exchange for buying the bond”. Essentially, a bond is an IOU. Junk bonds, specifically, are debt securities which are issued by companies or governments which are struggling financially. As a result, they carry a higher risk of default and are poorly rated (BB/Ba or lower) because of it. Usually these bonds are unsecured, meaning that if anything goes wrong you get repaid last (just before shareholders).

To compensate for their higher risk, companies issuing such bonds offer higher interest payments to potential bond holders. The higher the risk, the higher the yield; this is why junk bonds are also called “high-yield bonds”.

In really big LBOs, where even all the debt offered by banks or institutional investors does not suffice, junk bonds are often used as a quick way to raise extra finance. Although many believe that junk bonds are just an extra unnecessary burden to leveraged buyouts, they do have the capacity to further incentivize management to reduce costs and improve company performance in key areas . Nevertheless, following the financial crisis, dangerous financial instruments were not so well received anymore and the use of high-yield bonds in LBOs is not as common as it used to be. Funds have decided to take advantage of alternative funding methods in the debt capital markets by issuing bonds that rank “pari passu” with senior lenders (known as pari bonds).

A way to structure a deal using borrowed money

Having said this, how does a buyer actually secure the money and offer security in a leveraged buyout? Well, after the buyer has convinced a bank to lend them money, they have to give the bank some security. Buyers then put up security against the seller’s assets. This is odd because the buyers are essentially promising to pay out with assets they don’t yet own. Once this is done, the bank is said to have a “charge” over the seller’s assets and can take possession of those assets if the buyer defaults on its payments. After bank payments have been obtained, the private equity fund pools together all its other financial resources (money they received from issuing junk bonds, their own equity, money from subordinated lenders) and asks its lawyers to set up a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) which it uses to purchase shares in the target company. Essentially the buyer and seller are then “merged” into one new operative company. This new company will be “highly geared” (ie burdened by a considerable amount of debt because of how the financing was structured), meaning that if and when it starts generating money if has to first pay off the money it owes plus interest payments.

Who doesn’t like LBO’s?

Although private equity houses may argue that they are just promoting the “creative destruction” that the economy needs, many would rather see companies with a strong capital base as opposed to companies sinking in piles of debt. This is because the more debt you have the less you can do. You have to be super careful around expenses, especially if the buyout was funded by a lot of cheap debt. Without debt a company can focus on other stuff like expansion for example. Expansion creates more jobs, and new products. All things it couldn’t do if all its focus was geared back towards paying all the debt it owed.

One of the biggest critics of LBOs financed with cheap junk bonds was Ted Forstmann, CEO of Forstmann Little & Co, a PE house which back in the 80s was pretty well known. He was famous on Wall Street for being the only professional PE asset manager who refused to engage with junk bonds. He was firmly convinced there was nothing truly good about them and they only served to “saddle American assets with billions of dollars worth of debt; debt which had virtually no chance of being repaid”.

Lawyers in Private Equity

Having given an overview of the industry, I can now discuss the importance of the role held by lawyers who operate such transactions. In fact, were you to ask: how are lawyers involved? Who do they act for? My answers would be: “they are everywhere and they act for everyone\”.

Depending on who they act for, lawyers will have to provide different services.

For example, say they act for the management team of the target company. In this case, they get to draft the management agreement which will govern the new company, alongside an agreement specifying exactly how the new company will be run and controlled. In the case of a takeover where various bidders are involved, they may need to counsel board members on how to navigate their complex legal and fiduciary duties.

Acting for the Private Equity House

Law firms who act for the private equity firms, as opposed to the target company, also have a great time as they may work with the private equity house throughout the whole lifetime of the fund, from its structuring to the exit. This also means that a variety of practice areas get to be involved in order to ensure that every single stage runs smoothly.

First of all, fund lawyers will be needed whenever private equity firms decide to launch a new round of capital raising for new investments. In terms of structure, lawyers will have to make sure the fund is set up to provide limited liability for investors and unlimited liability to the GPs of the private equity house (as discussed above).

Then come the tax lawyers. They will ensure that the fund is structured in such a way that it will avoid suffering from any tax law repercussions, as well as making sure the fund is structured in the most tax efficient manner possible.

Competition lawyers may then come into play for when the target company has been identified by the private equity house and the latter wants to get pre-merger clearance to ensure the operation can proceed.

Corporate lawyers will draft the merger agreement and finance lawyers will liaise with banks and other underwriters to ensure that all debt documents are in place.

Employment lawyers will need to conduct the appropriate HR due diligence as employment agreements, individual contracts and retention or severance agreements between the company and its managers and employees may cause havoc if not considered appropriately. New compensation agreements may also need to be negotiated prior to the acquisition.

On the other hand, more general due diligence, which will be what trainees will be mostly dabbling with when participating in these deals, will entail checking that the target company has no outstanding litigation which may make it vulnerable to lawsuits, that all past and current contracts have been adequately reviewed and potentially renegotiated, and finally that any valuable intellectual property is included in the acquisition. Basically, lawyers have their hands full.

Also don’t forget that even if the private equity market tanks, like it did after the 1980’s LBO fiasco, this isn’t necessarily a problem for the legal profession. This is because, selfishly speaking, when things go wrong for the rest of the world (in this case companies), someone has to fix them (in this case, lawyers). Think of it this way; when the economy is booming and everyone is buying, private equity, M&A, banking and competition lawyers will have lots of work. But when a company or a sector goes bust, it is restructuring and litigation that come into play, meaning lawyers still have lots of work. This kind of strategic thinking is reflected in the dominant practice areas of some of the biggest US law firms. For example look at Weil and K&E, both are not only PE powerhouses, but are also extremely strong in restructuring and litigation.

Which law firms dominate this sector?

For those of you who thought the answer was “US” firms, you were right. Considering private equity is their flagship practice area, it isn’t surprising that Weil and K&E are probably the two most renown US law firms in the UK when it comes to private equity. But other law firms such as Latham & Watkins, White & Case, Ropes & Gray, Simpson Thacher, Davis Polk and Skadden also enjoy a strong reputation when it comes to this kind of work. US lawyers tend to be more specialized in high-yield debt because these kind of financial instruments, as I already mentioned, originated in America; and so they use this expertise as their selling point in European markets. For example, when Latham arrived in London in 1990, the firm leveraged its US clients and high yield expertise to build its UK practice. The firm also used its existing relationships with banks, including JP Morgan, Deutsche Bank, and Credit Suisse to secure work in the city. This is an area the magic circle has long struggled to compete in, especially when the European high yield market boomed after the financial crisis.

Private Equity today

Currently the message we are getting from the economy is that private equity lawyers will definitely not be out of work in the foreseeable future. A recent article from the Financial Times in June 2019 revealed that dealmaking activity in the sector is at its highest level since the 2008 financial crisis (accounting for 13% of global acquisition activity so far this year) and there seems to be “no end in sight to this buyout boom”. Leveraged buyout shops such as KKR and Blackstone are sitting on huge amounts of cash (also called “dry powder” in the industry) which they are eager to spend. This money is the result of successful fundraising combined with the record low interest rates which make the cost of borrowing money to finance takeovers ultra cheap. Stats tell us there are around 2.5 trillion dollars floating around in this market which need to be invested.

On top of this, current trends suggest that right now staying private is more alluring than going public. This might seem unusual considering that once upon a time going public was the be all and end all for a company. But if we think about it rationally, it is actually easy to see why: firstly, public companies have to succumb to all the rules and regulations which (rightly) force them to account to the public to whom they are selling their shares. This means a lot of paperwork and a lot of monitoring and compliance work.

Second, businesses are living through a decade of change, where issues such as sustainable investment, equality, diversity, populism, essentially issues which were never cause for concern in the past, now have the ability to send their shares soaring or drive them into the ground. Any small scandal could pull the fatal blow.

On the other hand, being private means you don’t need to account to the markets, you don’t need to keep investors constantly happy by finding ways of boosting up your shares (eg by forcing companies to issue share buybacks, see Apple) and it means that scandals may not hit you as hard (they may hurt your reputation but not your pockets).

Private equity is complex, challenging and most of all, cool. I hope this lengthy report (alas 12 pages are one too many for this to be called an ‘article’) managed to keep your attention, but most importantly, I hope that this read has marked the end of the vicious “nodding and pretending to understand” cycle which most of us, whether we admit it or not, have at least once found ourselves in.

Ginny is a member of TCLA’s writing team. She is Italian, having lived in Milan until the age of 16. Ginny recently completed a Combined Honours in Social Sciences at Durham University and begins the LPC in September 2018.